Making digital twins a reality at LAAS-CNRS

Interview with Georges Soto-Romero

Innovation is not only a question of university degrees and studies – it also requires the freedom to dream, the willingness to learn from mistakes, and the courage to persevere. Georges Soto-Romero of the LAAS-CNRS research laboratory, specialized in system analysis and architecture, shares his experience in working with an enthusiastic team to make the concept of the digital twin a reality.

How did you begin working on the idea of a 3D scan of an athlete?

It dates back to 2014. I was one of the scientific co-supervisors for a thesis with the French Cycling Federation (FFC) and my lab, the Laboratory for Analysis and Architecture of Systems (LAAS-CNRS), on the effect of the cyclist’s position on the bike. The thesis was published in 2017 and this gave us an opening for many collaborations, some academic, others industrial. So, 2014 was the starting point of the FFC–LAAS partnership and in 2016 we made our first publication on the use of 3D scans and computational fluid dynamics for cycling aerodynamics.

When did you, Antony Costes and Emmanuel Brunet begin toying with the ideal of a digital twin?

We met in 2015 at an event at the University of Reims. Antony was PhD student on biomechanics in our lab. Emmanuel Brunet was in charge of research development at the FFC. This was the beginning of our magic trio, where our scientific dreams began to take shape. We started ranting about everything we could do around the bike, the equipment and the athlete.

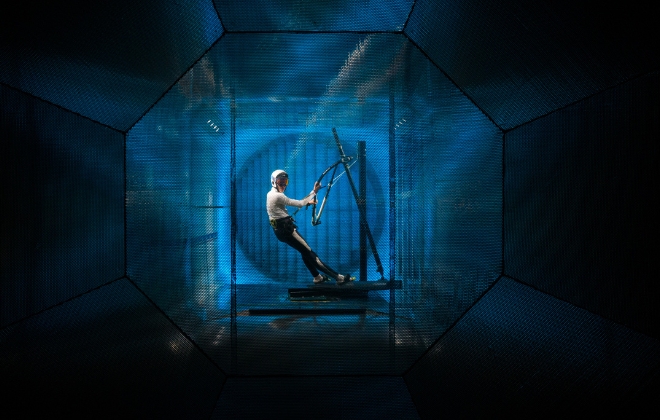

Antony served as our beta tester. We scanned him from head to toe, bike included, equipment included. We used talcum powder to improve the 3D scanner results, although it’s not usual to fill a world-class athlete and his equipment with talcum. Worse yet, we weren’t able to choose the 3D scanner we were using for that first experiment so it turned out to be a failure, but we didn’t give up. Finally, LAAS acquired a 3D scanner in 2016, and then a more advanced one in 2023. We also began to explore digital wind tunneling, a technology that ALTEN masters very well.

When did ALTEN become involved?

At the end of our preliminary study in 2016, we said to ourselves: “Great, now in France we can scan athletes and make digital wind tunnels to assess the aerodynamic performance of an athlete in competition.” In 2018, we managed to fund an intern from the engineering school, INSA Toulouse, who made us a database of several athletes. When they recruited Antony, the ALTEN Group joined our partnership and more things took shape. In 2021, we entered into a public-private partnership with the ALTEN Group and the permanent team. Then, our dream of so many years earlier started to become a reality.

How unusual was this encounter between science and sports at the time?

We were interested in popularizing science. We prepared a CNRS slide show that’s still online, titled “Cycling is also science.” It may sound obvious now in the midst of preparations for the Olympics, but in 2016 it was rather premonitory.

What is your feeling looking back?

Today we’re bringing to fruition projects that, without Lucas Limousin, Yann Nival, Sebastien Ricciardi and many others from the ALTEN teams, would have remained nothing more than dreams – things we would have liked to do. With the Olympics around the corner, it’s important to have made those dreams concrete. Now, you can say to an athlete: “Careful with this position. This equipment, you need to optimize it in such and such a way.” And that’s an incalculable contribution because the athlete is always looking for performance and speed. Being able to respond is important. In short, now we’ve got the hang of it. Before, we made academic research, and proved that it was possible. Now we’ve mastered the technology.